Brownfield London land is a case study of economic distress. Transactions are down 90% in the last year. There’s lot of chatter as to what’s driving the market down. Here’s my take.

Benchmarking land

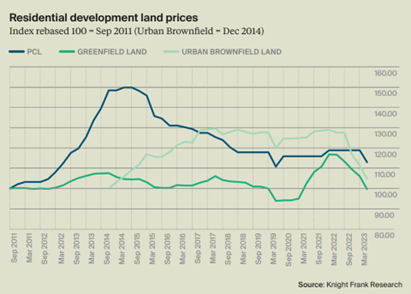

Land values are not easy to benchmark but over the last few years the real estate sector has got better at tracking value. Knight Frank’s (KF) latest UK brownfield land value index reported falls of 18% in the past year.

This is the largest fall on record. Sounds dramatic? Luckily for those of faint heart KF only started producing the index in 2011. The troughs of 2008 are not included.

What’s driving land value down?

There are three drivers which have impacted the development sector and the index in my view doesn’t reflect the extent of the fall.

First, the impact of the government’s flip flopping on the threshold for secondary means of escape is yet to feed through to prices paid for land. There is typically a 3-5% loss of net saleable floor area from an additional second core.

Less revenue, more cost and on an appraisal, the impact is around 20% on land value (or if you’ve already bought your site, your entire profit). That’s a big ouch. There are sites out there which could take years to unravel.

You’ve then got two other big trends. First, build cost inflation has been rampant since the end of lockdown. Second, and as a direct reaction to the inflationary pressures, the Bank of England have begun hiking interest rates.

When I run these impacts through a conceptual scheme of 100 homes, to maintain a commercial return you need to reduce land value by nearly 80%.

On the revenue side of the ledger and with many sites now sold for Build to Rent, punchy rental growth has cushioned some of the pain and in theory developers can renegotiate S106 obligations to improve viability. However, there’s no getting away from the damage that has been sustained.

A changing dynamic

Land value slides are not just a post Covid/mini budget trend. London “Res Dev” has been hit from all sides: taxation changes, Brexit and more complex viability testing effectively capping profits and reducing flexibility of exit. That’s why most housebuilders have exited the capital or are changing business models.

Back in 2014, the rule of thumb was that development land accounted for 25-33% of GDV. Now its hovering at 10%.

Land agents don’t tend to win much business when they advise potential clients that a site they could have sold in 2021 for £40m is now worth £20m. The play is to “reposition” or “repurpose” for more valuable bed uses such as student housing and co-living. When land is finite and with the planning system we find ourselves in a flight to other uses is inevitable. However, co-living and student are not immune to headwinds. Funding is by no means easy and there have only been three GLA referable co-living consents granted, ever.

Many landowners will of course sit on their hands once they have digested all that’s in front of them. Why move unless you have to? Particularly if the higher value living uses are not achievable.

The next few months

We’re shortly moving into election mode and there’s no hint of Government intervention like we saw in 2008/09 . Landowners waiting for a future pay day also need to be careful. The Government looks set on changing CPO to disregard hope value although the irony is that many brownfield sites are worth more in their existing use.

With rebasing ongoing and the government distracted, how long can the stalemate last? The lack of willing vendors is causing the widest bid-ask-spread I can remember, but as more forced sellers emerge transactions are likely to pick up in the next 6-12 months.

With it taking three years to get new sites into production there will always be tipping points and with developers set up to, well, develop, sitting still isn’t an option for many. At some point in the next twelve to eighteen months I expect the market to pick up but it will be a slog rather than a quick march out of this trough.