After many years on the touchline, it seems as if housing will finally be taken seriously at the next election. Fittingly it looks as if the highly politicised greenbelt debate will be central to this.

You have to look a long way back to find a party promoting greenbelt reform in their emerging manifesto. Yet despite the warnings of political suicide that is exactly what Sir Keir Starmer is doing.

The green belt, since its inception 70 years ago has often been preserved as a no-go zone for policymakers terrified of poking the hornet’s nest. For NIMBYs (a demographic that makes up a large proportion of the voting class) the greenbelt has become the living embodiment of their highly emotional and sensitive movement.

The affect it has had on its followers has been profound creating an informal coalition of national politicians, influencers and journalists dead against an evidence-based debate. Just this weekend Alex Preston in the Telegraph penned an article purporting to suggest solutions to solve the housing crisis. Not a single developer or house builder was quoted but instead an array of talking heads and NIMBYs with no actual experience of delivering homes were asked to opine. Land banking once again appeared as a chief concern with plenty of accusations of ugly housing on green fields.

When you peel back the layers, the drivers for stopping meaningful reform become clear. Take Theresa Villiers, a chief opponent of new homes in the House of Commons. Is it any coincidence that she resides over a constituency which includes the highest proportion of greenbelt land in London (27% of the overall area of Barnet)?

NIMBYS ARE WINNING

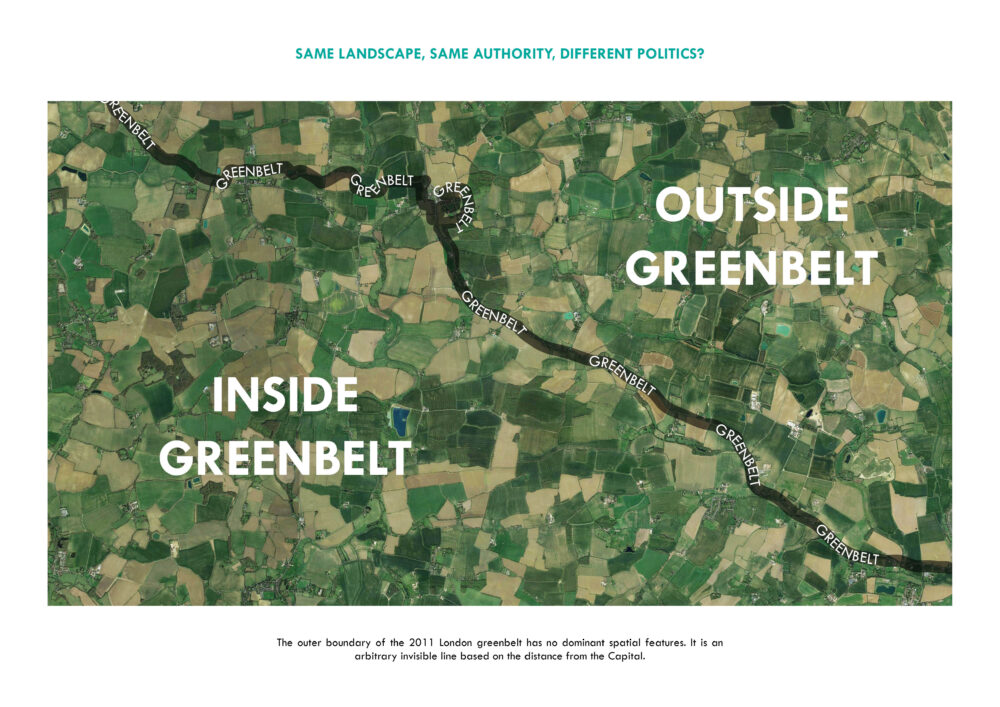

The political tiptoeing that has ensued has brought great success to the NIMBY cause. Today areas designated as greenbelt cover roughly 13% of the landmass in England, a figure that has almost doubled over the last 40 years. To put this in perspective residential buildings including gardens etc cover less than 2% of England.

While its most loyal supporters will argue the practicalities, to me the debate is simply a manifestation of a culture war waged by people who believe in a system where they are happy to see their house earn more through price inflation than their children’s salaries or where their right to a view is more important than a roof over someone’s head.

Where battlegrounds are most defined are often in areas where housing is most in need. Take London for example, despite a population increase of 20% since 1955, the Metropolitan greenbelt has largely stayed intact, equating to roughly three times the size of London itself.

You don’t need to be a genius to realise that if you have the most restrictive of policies in the most sought after of places you’re going to create problems. As a result, London has failed to grow at the rate needed and the unintended consequences are more profound than you may think. I could pull out any number of negative consequences to back this up. Whether its decreasing birth rates (see last post) or extortionate housing costs, we are now in a situation where cities such as London are at breaking point.

Why do I say this? Look at London rents as a proportion of income. Only once in history have they been higher than they are today and that was in the last days of Tsar Nicholas’s Moscow. Not a good precedent for things to come.

As our cities have changed, the greenbelt hasn’t. The sooner we loosen this noose from around our cities’ necks, the better.