The week’s new cycle has been peppered with government prevarication on HS2. Will they, won’t they. Which bits are likely to be sacrificed. Will the north lose out again. What about Euston. How has a nation once famed for its infrastructure fallen so far.

The health of a nation is often defined by its ability to deliver infrastructure. Back in the 1830s, Brunel built the Great Western Railway in just six years. Today, electrifying it has taken 12 painful years and counting.

As Nick Cuff quite rightly pointed out in August, the system is tangled in a mess of red tape, and here are some examples that painfully demonstrate this.

Consider the recent announcement to deliver a reservoir in Cambridge. Following the heat wave in 2022, Cambridge Water rather surprisingly announced its intentions to deliver long-term infrastructure.

Yet to the amazement of those who flicked through the dense proposal documents, the earliest which it could be delivered would be 2039. Even more astonishing, the process of public consultation and planning alone is estimated to consume 7 years, excuse the pun. To put this in perspective, the Romans managed to construct Aqua Claudia in just 14 years in AD 38.

Yet beyond the humour of these comparisons, there’s a more essential point. Consider the Great Western Railway. The Great Western Railway Act was passed in 1835, taking just six months to go through parliament and in that same year Brunel started on site. Where would we be now if all of his projects required 7 years of planning and consultation?

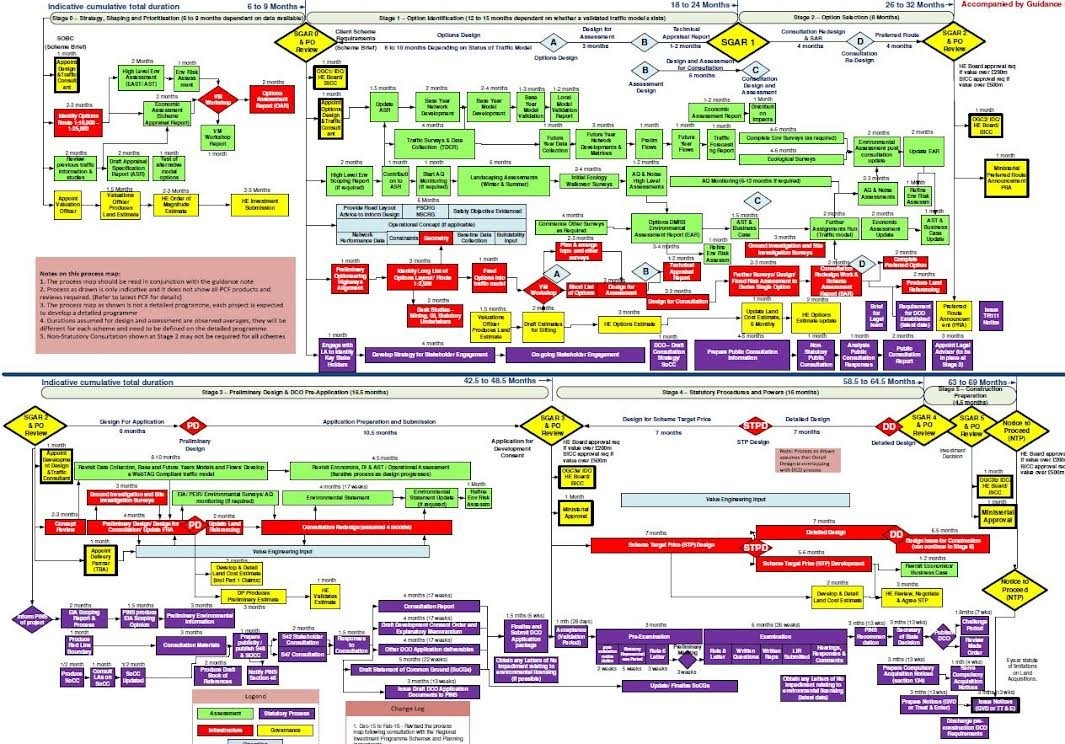

Image: diagram showing all stages in a typical highway scheme. It takes 5.5 years to the point at which you can put a spade in the ground.

Red tape aside, the issue has not been helped by a system that rewards a small minority that shouts the loudest. Whether it’s railways, roads or housing the issue remains the same.

Has there ever been a better example to demonstrate how far the Overton window has shifted than the recent Government suggestion that local homeowners should receive council tax cuts if they support new housing. Irrespective of one’s stance on the above, the shift in the system has led to a situation where the priorities of the hyper-local are often at odds with the broader national interests.

In a somewhat indirect way, Brunel recognised these issues when he said:

“I am opposed to the laying down of rules or conditions to be observed in the construction, lest the progress of improvement tomorrow might be embarrassed or shackled by recording or registering as law the prejudices or errors of today.”

Essentially, he warned against crafting a system that stifles innovation. Yet, today, we find ourselves entangled in precisely that predicament.

As I strive to wrap up this blog on a positive note, it’s essential to recognise that the inherent nature of these problems suggests they are not set in stone and can be tackled and even reversed with the right commitment. One can only hope that our decision makers will soon come to this realisation, though I won’t hold my breath!