Should the focus of planning reform be on the bigger sites and bigger players? Is it possible for small sites and small developers to make a meaningful contribution to housing numbers? Or is it too late to try and change what has become the default setting? This was the debate and the line of inquiry taking place over the summer in Whitehall.

Let’s start with what we know. There has been a material reduction in the contribution of SME developers. 30 years ago, they contributed 40% of housing supply. Today it’s around 12%. In London, between 2006 and 2016 there was a 50% reduction in small site development.

The decline has not gone unnoticed by policy makers. Indeed, supporting smaller builders has been a central plank of Government housing policy for at least a decade; most recently through initiatives such as the ENABLE Build loans. This £1bn loan guarantee scheme was launched to support finance for smaller housebuilders. But is finance what is actually needed?

Getting under the bonnet

There are differing theories as to why there has been a fall in SMEs. If we want to get under the bonnet and move beyond conjecture, data is required. Unfortunately, there is very little of it. There is no doomsday book detailing how many small sites exist in the UK. There is not a national wide data set on small sites developments and small developers.

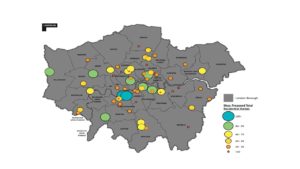

There is though, thanks to the GLA, a dataset of small sites that have obtained planning permission in Greater London – the only dataset of its kind. With this data the team at Pocket working in conjunction with our colleagues at planning consultancy Litchfields decided we had a chance to conduct a deeper analysis of the journey of small site developers and find out what’s happening out there.

The dataset consists of 675 small sites. By small sites we mean not micro sites – under ten homes, instead we mean over ten homes and under 150 homes or less than 0.25 hectares of land. When you remove outliers such as 100% grant funded schemes and permitted development schemes (different approval regime), you are left with the state of play for SMEs in Greater London. The team then undertook a deeper analysis at random of 10% of the data set, 60 sites equating to over 2,000 homes and averaging 33 homes per site to see if there were any common threads.

The main issues facing small site development

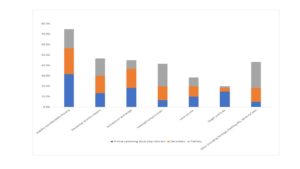

The analysis of the 60 sites sought to identify and codify the principle issues facing small sites. The findings were compelling. In three quarters of all cases, one of the biggest issues in the planning journey was affordable housing and viability. Moreover in a third of cases, there was a protracted dispute over the land value of a small site leading sometimes to deadlock between the local authority and the developer.

There were other issues, affordable housing was not considered in isolation. Residential amenity, density and parking are also considerations. However, design and architecture seemed to be an increasingly minor consideration with fewer than one in five cases giving detailed consideration to the quality of the building being delivered.

The lion’s share of time between the applicant and the Authority is spent negotiating affordable housing. Only 6 applications in the data set were able to achieve a policy compliant level of affordable housing. The result was the majority entered a viability process which appeared to lead to dispute, challenge and deadlock.

The clock ticks

Any small business knows that time is your enemy and no more so than in small site development where third-party funding is often the norm. The small sites in the sample size were taking on average a staggering 60 weeks to get planning permission. That is almost five times the statutory deadline. Just one of the sixty sites analysed met the statutory timescale and a fifth of permissions reviewed by the team took longer than two years to determine.

Much of this time delay was due to the complexity dealing with the viability and affordable housing approach. Ironically, those that actually did achieve good levels of affordable housing took longer to finally be determined due to the need to produce a more detailed Section 106 Agreement. The Section 106 process itself took an average 23 weeks to get through revealing that the journey to Committee itself was only part of the battle. There were some examples where the Agreement was taking years to agree.

Getting it right

One of the most surprising findings was that almost a quarter of the permissions reviewed from the random sample required two or three successive attempts to secure a planning permission. Half of the first-time permissions required major amendments during the determination. The amount of energy, time and money wasted trying to get through the planning system between developer and local authority is staggering.

Where we go from here

There is no one at fault here but the system itself which has created a constant stream of conflict. We are asking too much from small sites. Viability negotiations are protracted and complex. Small sites are just not able to meet the policy hurdles. The regime leads to regular and often intractable disputes over land value and affordable housing leaving little time to actually concentrate on what might actually be good design and place making.

This does not mean that affordable housing should not be delivered on small sites. However, it does need a simpler regime if it is to succeed. My next post will deal with this subject in more depth.